„Modern football“ is a buzzword. A buzzword with predominantly negative connotations in times of wobbling 50+1, increasing commercialisation, fragmented match days, etc.

But was football old before?

Antique?

Of course not.

Etymologically, modern means nothing other than „fashionable/according to today’s fashion“. Synonyms are adjectives such as current, new, contemporary and also mean progressive and something that has just become popular („modo“).

The question of modern football is about the phase in which football became popular with the mass of the population, not just a few nerds, and in which the original form was developed further.

From Empire to Commercialisation

In the Middle Ages and the early modern period, there was football in England, soule in France and calcio in Italy. In Germany, or more precisely the then German Empire, there was no football before the 19th century. It could not, therefore, fall back on forms that were already known and subsequently regulated. Football was unknown. And therefore it first had to gain a foothold in order to be modernised. For the word modern presupposes that there was already a previous form, an ancient form before that.

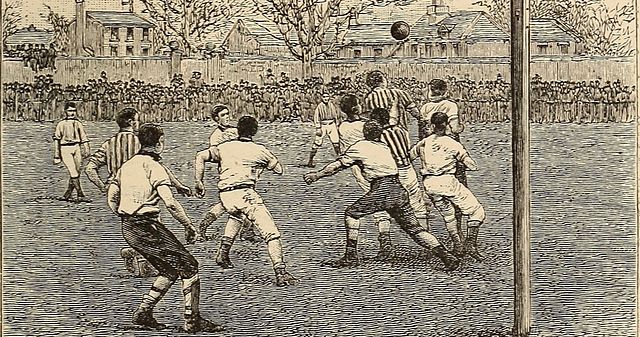

In the last quarter of the 19th century, sports that were popular in England, such as cricket, baseball and both football variants, rugby and (association) football, came to Germany. This was because the English living in Germany and English long-term tourists did not want to do without the much-loved sports, which also made it much easier to make contact with other English people in the area. During these decades, the regulated game of football developed from a sport for schoolchildren and students into a leisure and exercise activity that was firmly anchored in English society.

Germans who were in contact with English people – for example, doctors, language teachers, university professors or journalists – observed the sport of the English, sometimes took a liking to football and imitated it. This happened above all in the so-called English colonies in Germany. These were mainly in residential cities such as Hanover, Brunswick or Dresden, or in university towns such as Heidelberg or Göttingen. Englishmen were also frequently to be found in spa towns popular in the 19th century – Wiesbaden, Baden-Baden or Cannstatt are examples here – and in commercial cities such as Frankfurt, Berlin, Hamburg or Leipzig.

Modern football through English traders and tourists

It was the English living in Germany who made football popular in Germany.

This is important

One often reads that Konrad Koch brought „football“ to Germany, and this fairy tale is so widespread that there was even a cinema movie made about Koch. In fact, however, he spread rugby football in Germany and only turned to association football in the 1890s.

In Germany, gymnastics was the number one physical exercise. Having become popular in the early 19th century, gymnastics was closely associated with student fraternities and the idea of unity and nationalism. The sports that came from England, such as rugby or association football, tennis or cricket, were watched with suspicion because they came from England and were not of German origin, i.e. not part of German culture. Added to this were the translation difficulties of the English term sports, which was ultimately simply adopted into German usage. Technical terms such as offside, hand, to centre or goal were also adopted at first.

Modern football through political parties and the military

In November 1882, the Prussian Minister of Culture, Gustav von Goßler, issued the „Spielerlass“ (literally translated: „Play Decree“) named after him. He encouraged the Prussian municipalities to build playgrounds and to integrate gymnastics (later also sports) as a regular part of the curriculum. At the same time, school-free play afternoons were to be established.

Nine years later, on 21 May 1891, von Goßler and the Prussian MP Emil Freiherr von Schenckendorff founded the „Zentralausschuss zur Förderung von Jugend- und Volksspielen“ (literally „Central Committee for the Promotion of Youth and Popular Games“, or ZA for short. In 1897, it was renamed in „Zentralausschuss zur Förderung von Volks- und Jugendspielen“ (literally „Central Committee for the Promotion of Popular and Youth Games“.

The ZA was not an association of football lovers from different social backgrounds, but consisted primarily of members of the National Liberal Party and its All-German Association, thus mainly politicians, civil servants and members of the army. Their common goals: Strengthening German national consciousness, pro-imperialism.

Their primary goal, however, was not to politically appropriate sport, but rather to create a philanthropic, educational, military and social Darwinist mix, to raise a „healthy“ elite of sporty Germans and thus potential soldiers. Therefore, the committed personalities tried to fill the rifts between gymnasts and sportsmen and to mediate between them.

Gymnastics and sport were to exist in parallel and complement each other. To achieve this intention, the ZA tried to combine the individually acting forces in Germany in order to quickly reach the common goal. These included the

- „Zentralverein für Körperpflege in Volk und Schule, the Deutscher Bund für Sport, Spiel und Turnen“

(literally „Central Association for Physical Training in People and Schools, the German Association for Sport, Games and Gymnastics“) - the „Komitee für die Teilnahme Deutschlands an den Olympischen Spielen zu Athen 1896“

(literally „Committee for the Participation of Germany in the Olympic Games in Athens 1896“) - and later the „Jungdeutschlandbund“ (literally „Youth German Federation“), founded in 1911, in whose federal leadership many members of the ZA were also represented and which, like the ZA, was involved in pre-military training.

How did they try to achieve their goals? Well, through intensive lobbying in military authorities and school and city administrations, trips to England, regular publications appealing to different target groups and an enormous amount of advertising. Funds came from the Prussian Ministry of Culture and other German state governments.

The ZA ultimately achieved its goals of spreading the sports and making them national in scope.

Modern football through Deutscher Fussball-Bund (German Football Association)

The 1890s saw the emergence of a number of new clubs and also the first regional football associations, for example in Berlin (Bund Deutscher Fußballspieler 1890, Deutscher Fußball- und Cricketbund 1891). But while clubs in England were established communities, in Germany there was a high turnover in the clubs and therefore little cohesion among the players. Identification with a club had therefore not grown – this was inconvenient for the ZA. Its attempts to found an all-German association initially failed due to disagreements between the associations.

After several years of mediation, there was a new attempt to found a German federation in Leipzig at the end of January 1900. Now 60 of the 86 associations voted in favour of founding the German Football Association. The founding members were regional associations (Verband südwestdeutscher Fußballvereine, both Berlin associations and the Hamburg-Altona Football Association) as well as individual clubs from Prague, Magdeburg, Dresden, Hanover, Leipzig, Braunschweig, Munich, Naumburg, Breslau, Chemnitz and Mittweida – in other words, from all over Germany at the time.

In the years to come, the DFB’s match committee drew up uniform statutes and rules of the game based on the English model (issued in 1906) and there was regular play for the German Championship (from the 1902/1903 season) and the Crown Prince’s Cup (from the 1908/1909 season).

The DFB decided in favour of the national and against the cosmopolitan orientation. This was because they were given preference over the gymnasts in order to be allowed to use the parade grounds as a playing field. As a military sport, the stereotype of a footballer was charged with soldierly ideals: Fighting and sacrifice until the last minute, devotion to duty and loyalty to one’s team, as well as strength of character and idealism. Little has changed in this ideal to this day and it is also the reason why in Germany the legalisation of paid football has been rejected and stigmatised even more vehemently than in England.

Compared to Great Britain

Much has happened in Germany as it did in England, only some 50 years later, but not in this respect: while football became modern in England when it became legal professional football and many people found gainful employment directly or indirectly through the game of football, football became modern in Germany through the military and the soldierly ideal, i.e. the German amateur ideal. This did not change when professional football was also legalised in Germany about 50 years after its legalisation in England. That is perhaps one reason why in Germany the term modern football now has strong negative connotations and why the 50+1 regulation was not thrown out long ago. But it is perhaps also the reason why players who change teams frequently and for the sake of money are called mercenaries(!) because they did not remain loyal to their team until their last breath – deliberately put in very pathetic terms.

Meanwhile, the DFB’s membership grew rapidly, increasing seventeenfold between 1904 and 1913.

As I said, Goßler’s idea worked, football became a military sport. Even before 1910, the navy played its own football championship, and from 1911 the national army did the same. Like the ZA, the DFB became a member of state-run, military youth organisations such as Jungdeutschland, which was founded in 1911.

As a military sport, however, football now had to finally free itself from the accusation of being an un-German sport and remove language barriers. Therefore, from the 1890s onwards, there were repeated articles in newspapers, pamphlets and also books that introduced the English terms.

The great war followed, which contributed decisively to the first football boom in Germany. Football finally came of age in Germany.

Modern football: football enthusiasm becomes part of German society

Many German soldiers first got to know the game of football as a military sport during the First World War; they loved and lived it. Here, in the pure war of position, the games served primarily to psychologically stabilise troop units and lift their spirits, but also found general popularity among the non-noble milieus due to its class-levelling character. This enthusiasm did not end with the end of the war – on the contrary. Some played football in clubs from then on and many more became enthusiastic spectators. By 1920, the DFB had cracked the 500,000 mark for its membership. Now football began to become a mass phenomenon in Germany as well.

At this time, in the Weimar Republic, football took on a mediating role between the German population and the Reichswehr. The boundary between civilian and military sport was blurred. The word Kampf became a key term in the 1920s: combat games, Kampfbahn, Kampfgemeinschaft, etc. Football served as a pre-military field to introduce the coming generation to the virtues of soldiers, despite the prohibition of an army. In addition, many paramilitary associations disguised themselves as sports clubs, such as the boxing and sports department of the NSDAP. However, this was renamed Sturmabteilung, SA, by Hitler relatively early on, in November 1921.

While sports like football were a good outlet after the end of the First World War to compensate for the psychological strain of the war years, they harboured a clear potential for violence in the interwar period. Many of those who had experienced the game of football during the war played such unfair football or behaved so rudely as spectators by storming the pitch and threatening violence against referees and opponents that football not only gained widespread popularity in the early 1920s, but at the same time acquired a very bad reputation. The highly respected referee Peter Joseph „Peco“ Bauwens simply resigned in 1925 because of the behaviour of players and spectators at half-time of the match between 1. FC Nürnberg and MTK Budapest.

At the same time, football developed into a veritable economic commodity due to the large number of spectators. The DFB once again tried to restore this lost respect by linking it to the soldierly concept of honour – successfully. Modern football and professionalisation were far away at that time, but had long existed under the table.

The first radio broadcasts

In Germany, as in England, football was supported by journalism, the beverage and construction industries, betting shops, photography and sporting goods manufacturers. Cigar and cigarette factories as well as schnapps distilleries also profited from the sport, for it was customary in the spectator stands to fortify oneself with a drink from a hip flask or a cigar in between. New and in this case quite elementary for those interested in sport was the modern medium of radio, whose sales figures increased rapidly between 1923 and 1926. It was a win-win situation for both sport and medium: radio stimulated interest in following sport and those interested in sport bought radios. It is disputed when the first match was broadcast in Germany: Was it the match between Preußen Münster and Arminia Bielefeld on 1 November 1925 or the DFB final between SpVgg Fürth and Hertha BSC (late 1925), which was commented on by radio pioneer Bernhard Ernst? Whatever the case, the DFB initially supported the broadcasting of football matches, only to row back sharply in 1928: In order not to jeopardise viewer numbers and thus the clubs‘ income, broadcasting rights were only granted for the DFB final and three international matches. These clear restrictions led to fierce protests from viewers and indeed, from 1932 onwards, more football matches were again broadcast via radio; especially those matches for which a reduction in viewer numbers was not to be feared.

The DFB was not an isolated case. England and Sweden, among others, also had the broadcasts partly banned (Sweden) or discussed a general ban (England).

Modern football: Professionalisation becomes legal (for the first time)

In the mid-1920s, the first serious attempts were made in Germany to make football a paid profession. Because of the Dawes Plan (1925) and its subsidies, many cities began to build new stadiums in order to fill the municipal coffers with the help of football enthusiasm. In order to repay the mortgages more quickly and to utilise the stadium to capacity, attractive matches had to be offered and therefore football greats had to be attracted to the city’s clubs. In addition, Germany’s participation in the Olympic Games was possible again from 1925. The ambition to nominate a particularly powerful team was therefore great. Grants paid under the table had long been the rule.

The DFB stuck to its soldierly ideal of the footballer guided by honourable merit, not financial merit. Violators were threatened with disqualification from the championship and cup competitions. At the same time, many clubs wanted to be competitive with other countries. As early as 1925, the DFB had passed an amendment to its statutes that made it very difficult for German clubs to play against foreign professional teams. (The boycott was only lifted in 1930 under pressure from FIFA).

Due to the financial losses of the Great Depression, which hit the lower middle class (white-collar workers, skilled workers) in particular, there were renewed efforts to introduce modern football and professionalisation of football from 1929 onwards. Paying footballers under the table was by now the norm, but the DFB continued to stick to its principles. What’s more, in August 1930 it banned 14 Schalke players and also several Schalke officials and imposed a hefty fine of 1000 Reichsmarks on the club. The reason: Schalke’s top players were workers in the Consolidation pit, but were only entrusted with lighter tasks and thus did not have to work underground, but received significantly more pay than their colleagues.

The punishment as a deterrent for all other clubs completely backfired for the DFB: many other successful clubs pressured the association to withdraw the punishments and threatened to leave otherwise. The West German Football Association demanded a separation into amateur football and professional football. The DFB still refused, but when in 1930 the German Professional Association was founded within the West German Football Association and a Reichsliga (founded by sports journalists) was established, it relented. Schalke was exempted from the draconian penalties. But modern football and professionalisation was not yet legalised. The clubs‘ insistence remained and two years later the DFB probably feared the division of football so much that, like Alcock in England about 50 years earlier, it legalised the sport of football in order to then be able to control it better. But the Reichsliga planned for 1933 did not come to pass. The National Socialists were not directly to blame for this; professional sportsmen might even have accommodated them. No, Felix Linnemann, who had been chairman of the DFB since 1925, was entrusted with the management of the football department in the German Reichsbund für Leibesübungen in 1933 and directly reversed what he saw as the forced legalisation of professional football.

Modern football: Professionalisation football becomes legal (again)

In 1950, even before the DFB was re-founded, the delegates‘ meeting of the national associations decided on a contract player statute to legalise paid football. A player who pursued another profession was nevertheless not allowed to receive more than DM 320 per month, i.e. no more than the salary of a skilled worker. The annual salary was used to calculate the transfer fee. This always included a guest match with the new club.

Modern football and professionalisation were far away again at that time.

Then, in 1954, Germany surprisingly became world champion. In the following years, however, the importance of the national team declined noticeably due to a lack of success. Many players moved to clubs abroad, where modern football and professionalisation had long been established and they received higher salaries. For example, to Italy, where Helmut Haller (1962-1968 FC Bologna, 1968-1973 Juventus Turin), Karl-Heinz Schnellinger (1963-1964 AC Mantua, 1964-1965 AS Rome, 1965-1976 AC Milan) or Horst Szymaniak (1961-1963 CC Catania, 1963-1964 Inter Milan, 1964-1965 FC Varese) played. To counteract the trend, the DFB decided at its 1962 national convention to introduce a professional players‘ league, the Bundesliga. In addition to amateur players and contract players, there were now licensed players who could receive three times the salary of contract players and collect part of the transfer fee. But the regulations were still quite restrictive in the 1960s, which is why only 34 players are said to have played football as a full-time profession in the first Bundesliga season. They needed a good reputation, but were not allowed to lend their name for advertising purposes and thus receive further wages, and the total remuneration from wages, hand money, bonuses and transfer fees was not allowed to exceed 1200 DM per month.

For the DFB, the introduction of the Bundesliga was worthwhile: the national team was successful again and since many households already had a television in the 1960s, the DFB was able to finance itself through television broadcasting fees, advertising revenue and sponsorship money.

For contract and also licence players, playing football within the limits set by the DFB was not profitable and so it is not surprising that in the 1970/71 season there was such a big bribery scandal and the DFB was once again forced to rethink. In 1972, the market was opened up – since then, the incomes of professional footballers have been rising continuously. The liberalisation of the electronic media and the Bosman ruling of December 1995 have further strengthened this effect.

Conclusion: Modern football through eventisation and tactics

But when did modern football actually enter Germany? Depending on how you look at it, there are three possibilities:

- if you link modern football to general national enthusiasm, it was the First World War.

- if modern football and professionalisation are associated – and its consequences, it was the 1960s and 1970s, since the first legalisation in 1932 lasted only a few months.

If, on the other hand, the term „modern football“ is taken as a starting point, the beginning is in the 1980s. Until 1976, this term did not even exist in German-language literature. Since then, there was a brief minor peak from 1987 to 1988, which was reached again from 2002 and surpassed at least until 2008.

Was the first accumulation of the term at the end of the 1980s due to coach Arrigo Sacchi’s move to AC Milan and the idea of play he established there? Was this event actually so appreciated in German-language literature? Or did it have another cause? Unfortunately, I don’t have an answer to that.

Pingback: Modern football around 1900 -