On 19 February 1899 the Wiener Allgemeine Sport-Zeitung[1]Cf. NN: The Oxford team in Vienna. In: Allgemeine Sport-Zeitung [Vienna], 19.02.1899. p. 192. Last accessed: 04.03.2018. brought attention to the travel of the Oxford University Association Football Club to Austria for matches in Prague and Vienna during the Easter holidays.

Oxford University AFC was 1899 a very successful club of the Football Association, still existing in 2018, but now playing in the league of the football teams of British universities and colleges of the Midlands region (around Birmingham). The matches against the Deutschen Fussball Club and Slavia (both from Prague) took place at the end of March, the matches in Vienna against a „mixed [nation] team“ and „German [Austrian] team“ of the Athletik-Sport-Club at the beginning of April. The article also introduces the players of Oxford University AFC with information about the previously attended college, size, weight, position and other sports they played.

At 3:30 pm on 2nd April and 3rd April the matches were played in the Prater (now Ernst Happel Stadium).[2]Cf. NN: The Oxford team in Vienna. In: General Sports Newspaper [Vienna], 02.04.1899. p. 352. Last accessed: 04.03.2018.)

The game report was full with enthusiasm for the English combination game, which for all spectators and also English players of the Athletics Sports Club had been unrealistic.[3]Cf. H., J.: Der Fussballkampf – Oxford – Wien. In: General Sports Newspaper [Vienna], 09.04.1899. p. 386. Last accessed: 04.03.2018.)

„[…] The Oxforders shone due to their individual training, which fit harmoniously into the framework and enabled an interaction that let oneself get carried away. We faced something new, something unexpected. This ball playing technique, this fine tactics – the result of a cunning and lightning combination – that hasn’t been seen on the Continent yet; it was simply cute to see the astonishment our players saw three balls of the Oxford fly into their own goal in the time of two minutes without being able to seriously resist it! […] The playing style of the Oxforders was absolutely fascinating. That German professor, who last year let go of an armored combat brochure against the ‚brutal‘ football game under the title ‚Fussluemmelei‘, certainly never saw Oxford students playing! What he sees can only have been German malapropism, which – also with us – was kicking the ball with strong kicks in a huge arc over half the lane. But the Oxforders didn’t play such a thing, and it became obvious to us that the ‚rough kick‘ in the football game does not remotely have the role that has been ascribed to it so far on the Continent. Every witness to the Oxford game will admit the aesthetics of the game have not been neglected.

Even the first steps left no doubt that the English proceeded according to a fixed, well-considered system, in which everything is calculation, not even the smallest step is left by accident, to the difference between the completely unregulated way of playing of the Viennese based on accidents and the dexterity of the individual.. What the English teach us most of all was that the ball must not be kicked in the air, but rolled. That’s the quintessence of the game. At the kick-off a player tries to get the possession of the ball. Once this has happened, the entire English field takes the ball and positions itself so skilfully that one gets the impression of a siege line. The ball rolls comfortably for a few seconds flat along the ground, often through the legs of the opposing people, who usually miss their target with their long kicks. If the rolling ball has, as intended, attracted a larger group of opponents, they soon become aware that they have been lured into the trap. For before they know it, the ball has been delivered to the right or left at lightning speed, usually rolls unchallenged, from man to man, all the way outside, and you can already see how the English surround and block the ball by their three, four players. Usually one of them takes the ball from him, a powered ’shot‘ and the ball flies unstoppably behind the stunned goalkeeper into the goal. The ‚passing‘ of the ball is an important point in the tactical game plan of the English. In the majority of cases, the same is a feint, intended to deceive the opponent in relation to the direction of attack.

If the Viennese, as mentioned, were looking for their main strength in kicking the ball in wide and high arcs, this was welcome to the opponents because in this case they could observe the ball best, so the English tried again, if possible, to stop the flying ball with their whole body with the head, shoulders, back etc. – the hands of course excluded – and the well-known roll game progresses. The header, which also Wagner and Nicholson are able to play with great skill, is performed with admirable technique of the Oxforders. If the Viennese succeed in conquering the rolling ball and if the same of them had reached the opponent’s field with the usual vehemence – but mostly unfortunately quite indiscriminately in the target direction – the Oxforders had the opportunity again to use their highly developed running technique. In wonderful little jumps they followed, they emerged, as if out of the ground, at the endangered points, two, three, four blue-whites against a Viennese, so that one repeatedly had the impression the English team was twice as numerous as the opponent! Among the runners, Jameson in particular, with his great calf muscles, stood out, and none of the Viennese managed to keep pace.

The most ungrateful role was given to the Viennese playing on the first day. They had to pass the acid test against the dreaded Oxforders. The lack of any interaction played completely in Oxford’s hands, and although Wagner and Mollisch worked hard with contempt for death, there were always only fragmented forces against the closed English phalanx. In this, especially G. C. Vassal, who scored the most balls next to A. M. Hollins, showed his full skills. The ‚mixed‘ team of the second day had already copied many things from the Oxfordern, and now and then one could perceive contours of an interaction. Again it was Wagner, the tireless Nicholson, Gramlick and Windett who saved what could be saved, and Mollisch also successfully fended off many a ball from his goal. Shires was the only one who ever brought the ball into Oxford’s goal, but unfortunately the success did not count, because the ball had been shot from outside the field. Russel, the English goalkeeper, had to saved some shots, and he was able to prove his dexterity by even making the ball harmless at a considerable distance in front of his goal.

Exempla trahunt – it is usually said. The first thought that the gentlemen of the Athletik-Sport-Club should have expressed under the recent impression of the received defeat was to hire an English coach as soon as possible. A praiseworthy thought! Of course, the coach won’t do it alone. The matter lies deeper. In England the athletic education of the youth is a main factor of education, not so here. What has been cherished and cultivated there on the broadest conceivable basis for many, many generations is an unsystematic patchwork in this country. The Vienna Comité for the organisation of football matches, which has set itself the task of filling this yawning gap a little, has earned the gratitude of every Viennese who understands the educational role of sport both physically and morally, by incite the English team to visit our city under considerable pecuniary risk.

The competition was attended by a remarkably large number of spectators, including many high-born representatives of the upper tens of thousands, and the lively applause, in particular the original applause of the ‚golden‘ youth present, clearly proved that our understanding of sport is already growing today.“

(H., J.: The football match – Oxford – Wien. In: Allgemeine Sport-Zeitung [Vienna], 09.04.1899. p. 386. Last accessed: 04.03.2018.)

Statements as „What has been cherished and cultivated there on the broadest conceivable basis for many, many generations“ suggests a longer period of time than the forty to seventy years in reality. The Oxford club mentioned here only existed for 28 years.

Nine years later

Nine years later a Dr. Frey looked back on this game, which was decisive for the development of football in Vienna.[4]Cf. Frey, NN: Modern football game. In: General Sports Newspaper [Vienna], 31.10.1908. p. 1374.) He noted that Viennese football clubs meanwhile have learned the combination game, but have not yet cultivated all the elements of the English combination game, such as the interaction of defenders, midfield and attack.

„The year 1899 marked a turning point for the development of continental football. For the first time an English team, the Oxonians, faced our native [Austrian] players. It left ‚bloody‘ traces. The strikes were hit in mass. Playfully the Oxford strikers broke through the ranks of the Ours and it was astounding how easily they floated while the Ours struggled in the sweat of the face.

Soon we had the cause of their success out. Combination became the buzzword of all footballers. The training, so far a mere pastime, became somewhat more systematic. Here practice in dribbling the ball (literally translated: driving the ball in front of him), there a group busy with the art of interrupting the game, or headers. Some clubs even afforded an English coach. And last but not least, the annual games with the English brought us to where we are today.

In the past we were so weak that first-class English teams could be satisfied with the attacking game, but now we are so strong that we force all their defensive forces to take full action.

And now we were able to recognize what could be foreseen, however, that the combination of the attackers must correspond to a cooperation of the defenders, the latter should be able to arise. Manchester United showed this almost classically at this year’s games in Vienna. Besides the superiority of the individual players as such, this is the main reason why their middle and defense players nipped the attacks of the Viennese in the bud before they could unfold at all. Before this exemplary defence game of the English is presented, however, it is necessary to become clear about our defence and its shortcomings.

A number of single craftsmen can also develop an abnormal skill, a number of playing with normal skills, but cooperating can be competitors. In comparison to the English players, the weakness of our defenders lies in their lower individual ability to play and in the fact that they are only fragmented against the combining strikers. The relationship between backing and defense is similar to that between the [military] swarm line and the reserve. Only if both appear from the outset uniformly, they can fulfill their task. If, however, the reserve is so far behind the swarm line that it can reach it later than the attacking enemy, then the enemy will easily throw back the parts that occasionally face each other. What applies to war applies mutatis mutandis to peaceful betting as well. An example will show this: The opposite left wing attacks; the right midfielder throws himself against it, but is passed by the combining strikers because he only appears as one; for the moment he is finished. Now the right defender act, and since he can only use his individual power to defend, too, he will usually draw the shorter one. It is true that in reality this is not always the case. There are never completely equal opponents against each other and often a middle or defense player makes up for a tactical mistake by individual extra effort. This is even the rule here. But this does not mean that the theory is absurd. As in production, the highest principle also applies to sporting activity: Success can be achieved with the least possible effort from productive forces, here from physical forces.

Already this consideration of our current tactics shows that the defense must oppose something similar to the combination of the strikers. If, however, the cooperation of the strikers has the ball as an object, because it is supposed to push it into the goal, then this is excluded with the back team, because their task is the destruction and only in second place comes the supporting activity. Then it is clear: not the ball, but the players themselves are the object of the ‚combination‘. They must be related to each other in such a way they represent a ‚unity‘ by an appropriate, constantly adapting formation to the changing situation. Let us taking the example above: Again the enemy left wing attacks. The right half goes on and gets passed. But at the same moment the right defender backs up (literally: throws himself) towards the enemy, clears or at least stops the attack and gives the player the opportunity to retreat, while in the example above the by the opposite covered player was out of action for the moment.

For this ‚position play‘ the following scheme can be given: Let’s think of the players in their basic formation connected to each other by rubber cords. What happens now, if e.g. the own right wing goes over to the attack? The whole team is moved forward and to the right. Whoever is closer to the right wing will have to change his position more, whoever is further away from it will have to change his position less. The placement of the counterattack will then be analogous. This template shows the law of movement, which should control the movement and retreat of the teams in the match.

However, the mere knowledge of this principle will not be of much use in practice if the individual has not already acquired the skills necessary to realize this principle. A certain amount of physical strength and technical skill, though, will be desired by anyone the captain hires in the first team. [In the majority the captains were at the same time coaches and managers in Austria and also in Germany, called „Spielkaiser“- „Emperors of the play“ literally in English. I don’t know if Beckenbauer’s name as „Kaiser“ refers to „Spielkaiser“.] But the required mental abilities, which are necessary for the implementation of the position play, can be acquired only empirically, depending upon the plant and the competition practice.

How many moments does not determine the position of the individual? The situation of each time must be judged in no time, because fractions of a second play a decisive role in the betting game. First of all the player will have to know his own playing strength well, especially his speed. There are many defenders who overestimate themselves in this respect. Trusting in their speed, they press hard against the cover line, a long pass across the field, only one [Ludwig] Hussak needs to intervene and the misfortune is finished. Ferner it is necessary to know the playing ability of the opposite players as well. The ‚range‘ of the middle player, for example, depends on this and afterwards the defender will have to set up the distance and the interval as he staggers. Furthermore, it is important to know the speed of the opposing players, their playing method, whether they pass short or long, wing or three-inside-tactic forcing etc. and finally also natural circumstances play a role, e.g. the wind direction. [„Three-inside-tactic“ is how the 2-3-5-system was called in German speaking area before the Second World War.]

To judge these moments in every moment, to make the right decision immediately and to put it into action just as quickly, these are the two characteristics which, however, are seldom found united in our company: Experience and attention. Who follows the game – not just the ball – from the beginning, who overlooks his own and enemy position from time to time, who closely observes the playing style of his opponents, even if he himself is currently unemployed, will at least anticipate the coming in every situation, who, if he is to take action, will already be correctly placed and able to intervene successfully.In general, apart from subtleties, this law of the ‚position game‘ can be formulated as follows: Never stand on the same level, never unprotected exactly one behind the other; always staggered backwards, the front side protect the inside!

Dr. Frey.“(Frey, NN: Modern football game. In: Allgemeine Sport-Zeitung [Vienna], 31.10.1908. p. 1374. Last accessed: 04.03.2018.)

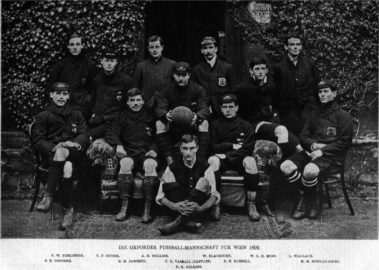

Fotocredits

Photography of the Oxford University AFC before his trip to Austria. In: Allgemeine Sportzeitung [Vienna], 25.03.1899. p. 323.

Fußnoten

| ↑1 | Cf. NN: The Oxford team in Vienna. In: Allgemeine Sport-Zeitung [Vienna], 19.02.1899. p. 192. Last accessed: 04.03.2018. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Cf. NN: The Oxford team in Vienna. In: General Sports Newspaper [Vienna], 02.04.1899. p. 352. Last accessed: 04.03.2018. |

| ↑3 | Cf. H., J.: Der Fussballkampf – Oxford – Wien. In: General Sports Newspaper [Vienna], 09.04.1899. p. 386. Last accessed: 04.03.2018. |

| ↑4 | Cf. Frey, NN: Modern football game. In: General Sports Newspaper [Vienna], 31.10.1908. p. 1374. |

Pingback: Inhaltsverzeichnis • Contents • Alles über die Fußballregeln -